View by Country and Subject

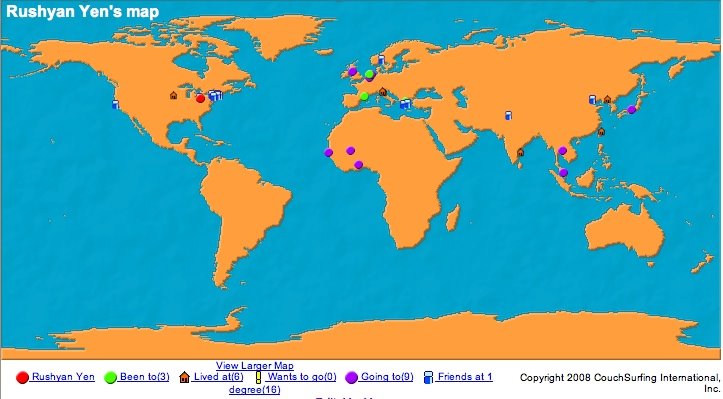

- America (3)

- Batik and I (4)

- Batik background (1)

- China (1)

- Ghana (4)

- Indonesia (7)

- Japan (26)

- Malaysia (11)

- Mali (6)

- Quarterly Reports (4)

- Senegal (1)

- sketchbook (1)

- Thailand (5)

- The Gambia (8)

- the journey of art (1)

- The Watson Fellowship (3)

- United Kingdom (22)

Saturday, May 8, 2010

Friday, April 23, 2010

Thursday, August 6, 2009

Quarterly report #4

Although batik has been adapted by fine artists in Europe as a medium of expression, it was the trade industry that first brought it over from Asia and later carried it all the way to West Africa. While Indonesians refused to accept the mass-produced “wax prints” that the Dutch and British tried to market back to them, these same textiles were so popular in West Africa that it would now be impossible to imagine its landscape without these colorful patterns and prints. This was the last stop on batik’s long journey and marks the end of my own year-long exploration of this ancient art form.

Like the marathon runner sprinting for the finish line, it was here that I faced the greatest challenges and made the most ground in understanding myself and the world around me. The physical difficulties of the excruciating heat and scarcity of water, the mental exertion of trying to make sense of the language and culture, plus the spiritual drain of guilt and sympathy I felt here all contributed to my growth as an artist, a person and citizen of the world.

Introduced in the 1950’s by Dutch colonialists who brought it over from Indonesia, batiks are a relatively new phenomenon in West Africa and artists here simply don’t have the expertise, materials or tools of their counterparts around the world. After seeing the exquisite rozome of Japan, the intricate batiks of Indonesia and the fine-art batik paintings in the UK, it was difficult not to look down on the simplicity of batiks made in this part of the world. Creating the highest quality batiks was never the main objective of this year however and the things I learned here went far beyond wax, dye or cloth. Making batiks in Africa taught me: to make use of every available resource and waste nothing, how to adapt new techniques into old traditions, the importance of family and relationships, and finally how I can contribute to society as an artist.

My adventure took off in The Gambia were I spent two weeks with batik artist Buba Drammeh and his entire extended family in their rectangular shaped “compound” made up of tiny rooms around a central courtyard. Most professions in this country are a family affair and the art of batik and tie-dye are no exception. Buba learned his craft from his uncle who learned from his father and so on down the generations. As Buba’s student, I quickly became incorporated into the family and was christened “Bingta Drammeh” to match my new Gambian identity.

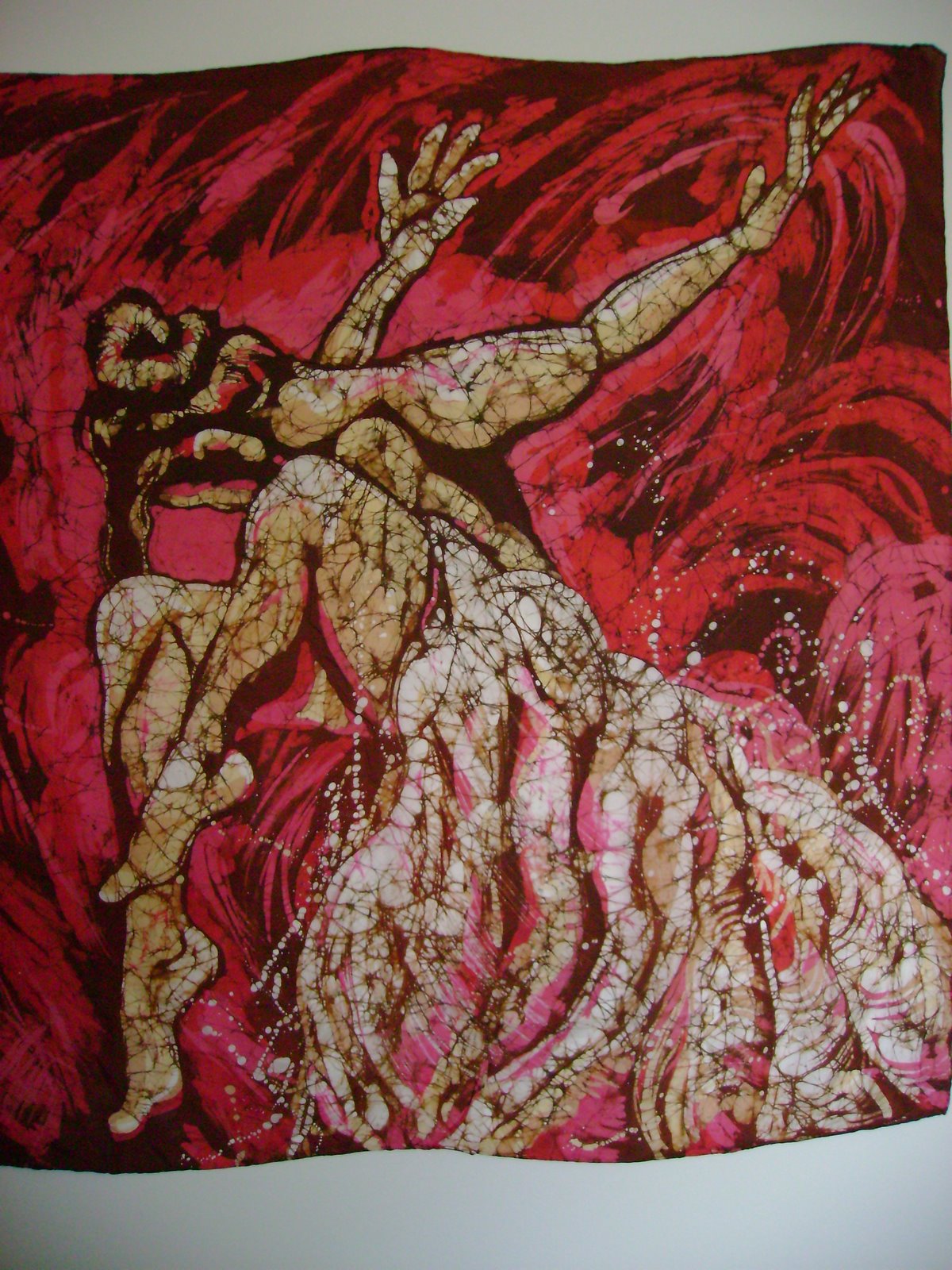

Even daily life is a struggle in this village with no electricity and very limited water so one can only imagine what it was like to make batiks in such conditions. The actual act of creation was easy compared to the time and labor spent gathering wax from beehives, building a fire, melting the wax, carrying jugs of water, boiling the water and even heating the iron with charcoal. The batiks I made here reflect the difficulty of life in rural Gambia and the strength of its men and women. While the lines and colors of my paintings may not be perfect, to me, they are all the more valuable for the hard work and struggle they represent.

From Buba’s village on the north shore, a short ferry ride to the other side of the country took me to natural dye expert Anita Whittle where I learned about kola nut/indigo dying and worked on my own pieces with an artist named Musa - one of the few dyers in Gambia still using and experimenting with these natural dyes. Not only has Musa’s line of work been passed down through the generations it is a business that the entire family participates in. Stepping into their compound, I was impressed at seeing sisters/daughters pounding Kola nuts, uncles/fathers printing wax, grandmothers stitching tie-dye cloth and brothers/sons dying the fabric as naked babies tried their best to amuse the workers. If only all families worked together so well!

Batiks in Senegal reveal the creativity of the artists and reflected or perhaps explained the more advanced development of Gambia’s neighbor on all sides. Instead of focusing on quantity they also value quality and look for ways to be innovative and unique in their work. Senegal is famous for its tie-dye and batiks here have benefited from the expertise of these fabric dyers. In spite of its role in the slave trade, the Island of Gore is now a center for arts and crafts and a gathering place for the most liberal-minded and creative of individuals. The colorful batiks and tie-dye that were on sale everywhere reminded me of flowers growing on ancient ruins, covering the horrors of this island’s terrible past.

The long, torturous bus ride to Bamako, the capital city of Mali was made worthwhile by the huge groups of fabric dyers I found working along the side of the road. Batiks here are considered a form of tie-dye and used solely as a method of making patterns on cloth with wooden stamps. The few batik paintings that I did see in the markets were imported from neighboring countries such as Senegal or Guinea. Malian textile artists are instead busy creating “bogolanfini,” the mud-cloth that Mali is known for. My studies with the internationally renowned Bogolan Kasobane group in the city of Segou was necessary to understanding this textile tradition which has influenced and been influenced by the newer batik technique. It was amazing to see its similarities with Indonesian batiks in particular which also value symbolism, meaning and the creative spirit in the creation of each piece.

From there, my newfound interest in mud dying led me to Djenne, the ‘birthplace’ of this medium and then Dogon Country, where the traditional dye methods have stayed alive. It was in this gorgeous land known for the villages hanging on cliffs that I was able to experience Malian spiritualism and symbolism to the fullest.

Finally, in Ghana, I encountered Adinkra, the only African cloth printing tradition that existed prior to colonialism. According to legend, it was introduced to the Asante people of Ghana following the capture of a rival monarch from the Ivory Coast by the name of Adinkra, who wore the cloth to express his sorrow on being taken to the Asante capital of Kumase. The name “Adinkra” thus came to mean “farewell” and the fabric became commonly used at funeral ceremonies to say good-bye to the deceased. Today, this cloth is an integral part of Ghanaian culture and symbols from King Adinkra’s robe are seen on everything from clothing to academic/political seals to billboards and other advertisements.

It was amazing to see how easily and fully batik could be incorporated into this older textile technique. Traditional Adinkra cloth involves the printing of designs with a black dye made from the bark of the “Badie” tree using stamps carved from sections of calabash. Since the ink is not fixed however, this fabric can only be worn for special occasions such as weddings, funerals and initiation rites. The adaptation of these same wooden stamps for the batik medium however, allowed the material to be made with colorfast dyes and opened the door for Adinkra symbols to be worn at anytime and for all occasions. The batiks I made in Ghana with artist Antoinette Ablordy are thus filled with Adinkra symbols—each with their own names, meanings, proverbs and stories.

Perhaps it is this pride in their rich textile traditions that has made Ghana the first country in West Africa to market their own wax prints as opposed to the imported ones from Holland or England. I was amazed when I first saw “authentic Ghanaian wax print” on the bottom of these fabrics instead of the “genuine Dutch wax print” label ubiquitous throughout the rest of West Africa - and further impressed to hear of not one, but four major Ghanaian companies for customers to chose from. The T.V. commercials and advertisements encouraging Ghanaians to support their countrymen by only purchasing locally made textiles is reflective of the patriotism of this nation which has seen so much development and improvement in such a short time.

It is not just the finished textiles that Africans should consider however, but all aspects of batik making. Almost all works of artwork or clothing in their country are the result of dyes imported from Germany, fabric brought over from China, and designs copied from abroad or geared toward foreign tourists. 200 years after slavery was abolished, it seems West Africa is still controlled by foreign entities. In spite of rich textile traditions such as tie-dye in Senegal and Gambia, Bogolan in Mali and Adinkra in Ghana, the most ubiquitous fabrics are still the wax prints that come from Holland or England. In order to truly be free and independent, West Africans must look toward themselves and not outside their country for their materials, tools and designs. I arrived to Accra just in time to witness the excitement of President Obama’s visit and hear the cheers from his speech which focused on the future of Africa. We listened as he spoke of the rich resources of this continent and the prosperity that is only possible if Africans help themselves instead of depending on foreign aid. Africa’s future, as Obama states, is up to Africans and the choice of a locally made batik is one step in the right direction.

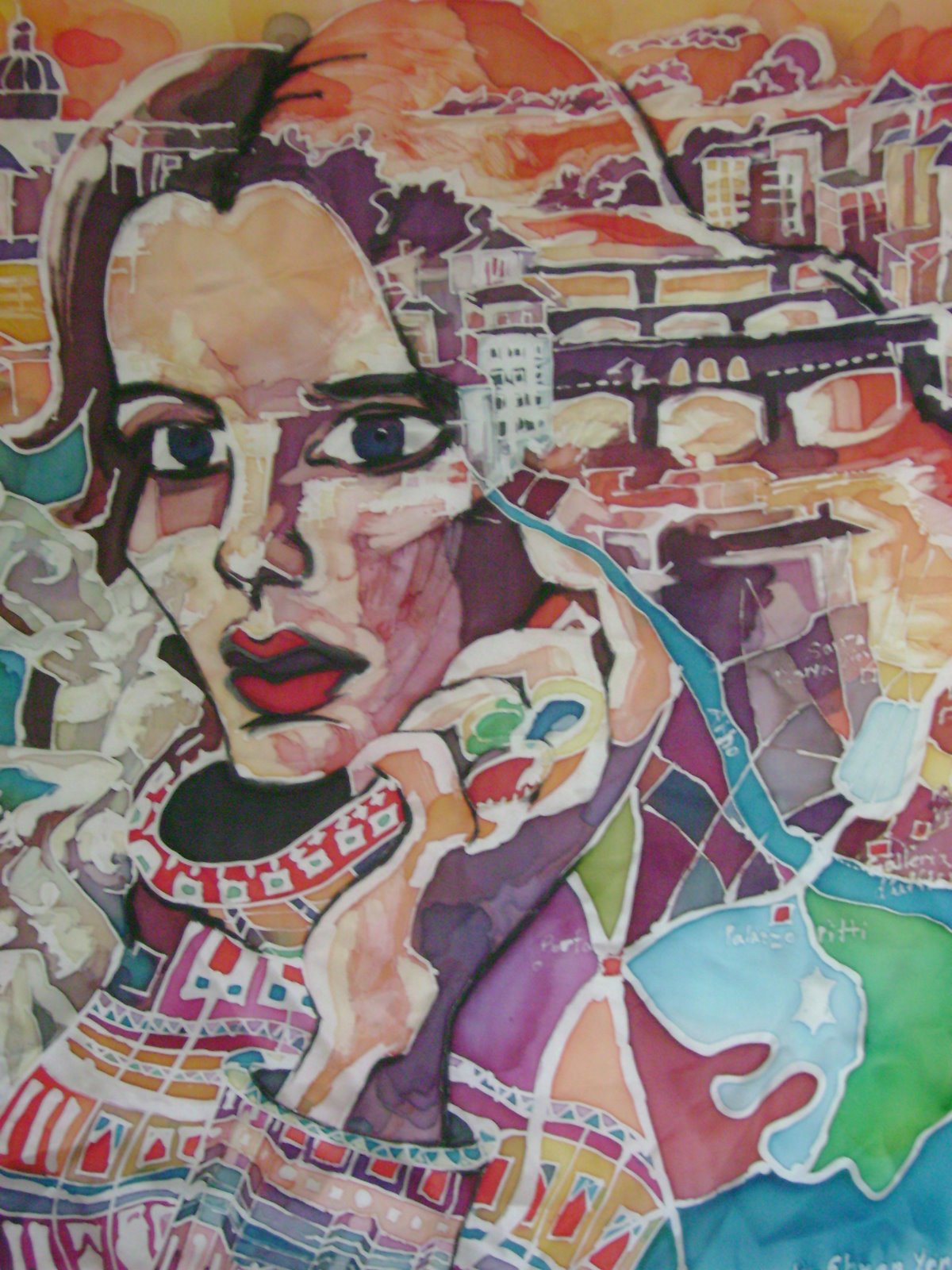

Thus, with the help of King Adinkra and his symbols, I bid farewell to Africa, my Watson year, and the incredible adventures and freedom that came with it. From Asia, to Europe to Africa, I successfully traveled for one year following an art form known as batik or rozome in order to understand the culture from which it came from, learn from the artists who created them and most importantly, make my own works from what I have seen and experienced in each country. What I found was a world full of places that have inspired me as well as people who have taught me more then I could have imagined. Before this journey, the world seemed so enormous, intangible and intimidating. After the incredible connections I have made across cultures, continents and languages, I have come to see that it really is such a small world after all and I am determined to do my part to make it a better place.

I began my Watson year as an idealistic art student with no idea of how to use my skills to help society, and now, at the end of the rainbow, I feel that I have finally found my goal. In the process of studying batik within various cultures and places, I discovered a need to help societies to develop in a sustainable and environmentally conscious way and furthermore, realized that it is through architecture that I can use art and design to meet the specific needs of individuals and communities around the world. With this realization comes a whole new set of goals to reach, work to accomplish and finish lines to cross. So while this may seem like the end of the road, in reality, it is really just the beginning of a grand new adventure and it was the Watson Fellowship that showed me the way.

Sunday, July 26, 2009

Cassava Paste Resist