The transformation of a blank piece of fabric into a work of art using wax and dye is the definition of a batik.

The end creation is a reflection of the artist and the

cultures and ideas that they are influenced by.

Every aspect of batik is rich in symbolism: the colors, motifs, and designs, as well as the way it is made, folded, and worn - an expression of the people who make and wear it.

The origin and nationality of batiks have always been questioned, though evidence of this ancient craft can be traced back to Egypt, Central Asia and India more than two thousand years ago. Although the exact birthplace and date are unclear, it is evident that all batiks tell a story or depict an event that reflect the current affairs, social moods or proverbs significant to the designer and the region that they are created in.

The origin and nationality of batiks have always been questioned, though evidence of this ancient craft can be traced back to Egypt, Central Asia and India more than two thousand years ago. Although the exact birthplace and date are unclear, it is evident that all batiks tell a story or depict an event that reflect the current affairs, social moods or proverbs significant to the designer and the region that they are created in.

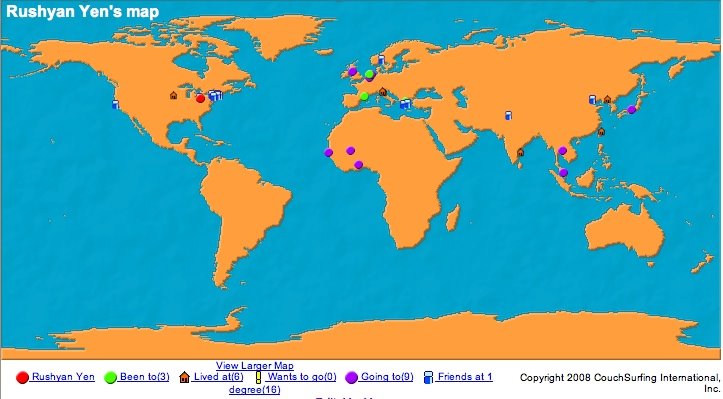

For my own journey into the world of batiks, I have specifically chosen to look at the designs created in Japan, Malaysia, Thailand, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Ghana, Mali and The Gambia. These are countries that have been touched by ancient trade routes between Eastern and Western civilization. Much like my own relocation from Taiwan to America, batiks also traveled from China to Europe through the Silk Road, and with the Dutch India Trade Company, spread all the way to West Africa.

From traditional Asian craft to contemporary fine art, batiks have changed and adapted to the individual touch of each of these nations. During my year as a Watson Fellow, I will work alongside artists from these countries to study how they have transformed foreign ideas into their own unique designs. As a fellow artist, I will take what I learn to create in each country my own paintings on cloth and see how I too can change and adjust with new places and cultures.

Japan is the first country to be influenced by the batiks of China and after fifteen hundred years, this Chinese influence has become inseparable from Japanese culture. The artists here have developed expert techniques in shading, control and luminosity that set these batiks, called rozome, apart. Even now, traces of their ancient Chinese influence can still be found in the ubiquitous kimonos and screens that color the landscape of Japan – glorious textiles where flowers blossom, lions roar ferociously, birds fly freely, mythical animals leap and grains of rice dapple the cloth.

From China, batiks also diffused to the islands of the Malay Archipelagos, bringing with them a bright new palette of colors to mix with the earthy indigos and browns of this land. It is here that this art form has been most extensively developed and practiced on a large scale, and where the word “batik” was invented. Considered the national art form, batiks have become an important part of Malaysian identity and a symbol of their independence. By developing unique aesthetics and designs, they truly have made it their own. Here, the figurative Chinese animals and flowers have morphed into more symbolic shapes to accommodate the Islamic ban on animal motifs. As I chart my path, the designs I make in Malaysia will be more abstract, but just as beautiful in their own way. The paintbrush I used in Japan will instead be replaced with the Indonesian-invented tjanting tool or tjant, and I will now draw or stamp my path instead of painting it.

The vein-like crackles of ink will also lead me to Thailand, where batiks have developed their own distinctive look, characterized by brighter, happier colors. Designs here are most often influenced by the sea, coral, fish, coconut trees and the nature seen in daily life.

With the chartering of the Dutch East India Company in 1602, batiks spread from the Malay Archipelago to the Netherlands. This is when East truly met West and where the full potential of batiks flourished. The curved lines and patterned surfaces of Asian tradition later merged with the bold colors and spontaneous forms of Western painting to contribute to the Art Nouveau movement whose design motifs are reflected on the colorful, decorative batik fabrics found here.

The United Kingdom and the Netherlands are where the craft of batik graduated to fine art and the most innovations are being made. Modern science has begun to make its own contributions to the production of this art form. I will join the artists here in Europe on their experimentation with the new chemical dyes and synthetic materials that science has invented. Together, we will explore new frontiers and draw fresh paths in wax.

It was on early Dutch merchant ships that batiks finally made it all the way to West Africa. Used as currency to be exchanged for slaves or gold, batiks are now integrated into African society. Despite their foreign origin, batiks have become widely recognized as “African” fabrics, whose unique geometric designs remain unchanged from the cultural background in which they came. However, the switch from traditional mud-painting to wax and dye reflect the difficult and quickly-changing environment which the Dutch colonists brought with them. Ghana, Mali and The Gambia are where I will integrate these unique designs into my compositions and thus transcend both the Eastern and Western cultures I have always been torn between.

It would not be a journey if there were no trials to overcome or monsters to defeat. My main enemy on this journey will be the many forms of language barriers I will meet along the way. Relying on the strength of my art, I am confident I will overcome these barriers to communicate in ways that spoken language cannot.

Under the heat of the south Indian sun during my summer at the Cholamadal Artist’s Village, I received my first lessons in the language of art. Engrossed in capturing the efforts of the fishermen as they pulled in their catch, I did not notice the old man behind me until he tapped on my shoulder and excitedly showed me his own sketchbook. Although I did not speak Tamil and he could barely understand English, we each presented our sketchbooks and in this way, told the story of our lives. Hesitantly at first, but with increasing fluency, we shared our knowledge of art and its techniques. Eight weeks later, my drawings were drastically improved. More importantly however, was the close connection I had made with Siddharth - a friendship created without the controversy and uncertainty of words.

I mastered the use of art to communicate across cultural and ethnic divides during my internship at the Art and Design Research Center for the Olympic Games this past summer. From its logo of five interlocking rings to the peace-dove as a symbol of the Olympic Truce, I witnessed the ability of images to represent the philosophy of building a more peaceful and better world though sport and the Olympic ideal. Thus, I gained a fluency in art - a weapon many times stronger than the ambiguity of words.

All travelers get hurt at some point and I am sure I will be no exception. Even in this aspect however, I am confident that art can pull me through. In Cortona, Italy this past year, I experienced first-hand the healing power of art. Developing tarsal tunnel syndrome in the ligaments of my lower leg during my first week in this hilly country was the most painful and frustrating moment of my life. Although I was in constant pain for a year, art became my therapy and not once did I consider returning home. Painting a portrait of Achilles pulling out the arrow from his weak ankle, I transferred my hurt onto the painting until the throbbing pain in my foot became only empathy in my heart for the agony of the man in front of me.

Even Odysseus had the help of the gods and the advice of oracles. My own expedition will require assistance in order to find the sites in which batiks and their artists have traveled and now live. The many responses I have received from batik artists to my letters of inquiry are proof of Betsy Sterling Benjamin’s own reply that “all batikers are brothers and sisters.” As a world-renowned batik artist and organizer of the 2005 World Batik Conference, her willingness to help and meet with me are itself evidence of this strong batik community.

Of course I would hope to give something back to this family who has already provided me with so much help and support. As I travel from county to country, the information and knowledge that I gain will be shared with the artists that I meet there. Techniques such as the sustainable batik process of my contact Robin Paris in Britain can thus reach other parts of the world. Emilila Tan is a premier Malaysian batik artist who has agreed to allow me to contribute to her magazine myBatik and communicate my experience with the international community. In this way I will share my gift of the Watson Fellowship and multiply it by a thousand fold.

With initial contacts such as The Batik Guild (based in the UK), the International Batik Committee (in Malaysia) and batik chat rooms like “waxeloquent1,” I will find my way to the artists who make batiks and the culture they represent. From all corners of my vast canvas will materialize the rich variety of batik styles, techniques, and processes I find. This meeting and merging of designs and patterns is what will inform the batik of tomorrow and open doors to other undiscovered lands.

These open doors are the questions that guide my Watson journey and entering them, I will find the answers that I seek.

What is the future and how has it been influenced by the past?

What are batik’s influences in contemporary artistic circles?

How does the present exclude or encompass the rich historical past?

What new inventions have the artists of this wide-ranging medium explored?

From the East to the West, the ancient to the modern, I will track the path of batik while trying to understand the fusion of cultures from which I come. That is how I will discover myself and thus be transformed.

No comments:

Post a Comment